A Taste of Mekong River Cruising

By Ted Scull.

Published Nov 2015.

Throughout my many years of traveling, I’ve found that river journeys have often provided deeper insights into a country’s culture and history than more hectic travel by road or flying from city to city over so much interesting territory.

Outstanding examples that I treasure are cruises along the Upper Amazon in Peru and Brazil; the Danube, Elbe, Rhine and Rhone in Europe; the Volga and connecting waterways in Russia; the eternal Nile in Egypt; the vibrant Yangtze in China, and our own Mississippi, Ohio, Columbia and Snake here in the U.S.A.

Recently, I added the Mekong River in Cambodia and Vietnam to my life-list, and although this river trip is still fresh in my mind, it probably ranks number one when combining all its alluring aspects. I greatly enjoyed the heavily trafficked waterway scenes, varied sights along the banks, intriguing riverside market towns, and the wonderful conveyance, a stylish riverboat that replicated an early 20th century Burmese steamer — with air-conditioning.

The British-owned Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, founded way back in 1865, once operated literally hundreds of river steamers along the Irrawaddy, Chindwin, and Salween and connecting tributaries in British Burma. By 1920, the firm ran the largest privately-owned fleet (650 vessels) in the world with the longest measuring 350-feet and licensed to carry up to 4,000 passengers. When the Japanese invaded Burma in 1942, the flotilla’s officers and crew scuttled the entire fleet so they would not fall into enemy hands.

After the war and Burmese independence, the fleet was slowly rebuilt. Fast forward to 1995 when a Scotsman named Paul Strachan, a Burmese history and literature scholar, seized the opportunity of running river cruises in Southeast Asia. He bought a 1947 Scottish-built riverboat named Pandaw to operate on the Irrawaddy River.

As the operation proved successful, he began constructing replica steamers in Myanmar (Burma) and Vietnam and bought the historic name — Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, with the company known commonly as Pandaw Cruises. The fleet, now numbering more than a dozen ships, plies rivers in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

Pre-Cruise Laos & Cambodia

Prior to joining the 64-passenger Mekong Pandaw in Cambodia, my wife and I visited Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital city, followed by Luang Prabang, the former Laotian imperial capital, and Vientiane, its current capital — the latter two sited on the upper Mekong.

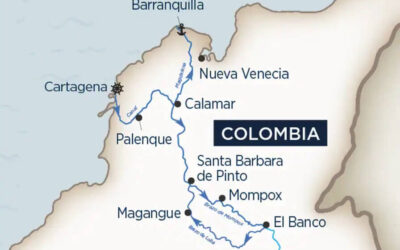

The river’s 3,050-mile journey begins at the edge of the Tibetan plateau, near the source of the Yangtze, passing through or alongside six countries and splitting into nine fingers as it drains through Vietnam’s fertile delta and out into the South China Sea.

Our Mekong river cruising tour began at Siem Reap, Cambodia, near the shores of the vast Tonle Sap Lake, the largest body of freshwater in Southeast Asia — one that expands its surface by a factor of six between dry and wet seasons.

Le Grand Hotel d’Angkor, built in 1931 by the French then occupying Indochina, became our luxurious base while visiting the ruins of Angkor Wat, the largest religious site in the world. Constructed in the early 12th century by the Khmers, the temple began as a Hindu site and then morphed into Buddhist, as it is today.

We entered via a causeway over a moat that surrounded the 203-acre sandstone complex and passed through the main gate. The place is utterly overwhelming with soaring stone towers, long galleries linking buildings, narrative-scene bas reliefs, and standing depictions of Buddha.

Angkor Wat represents the largest temple in this area that houses many additional temples in styles reflecting the influences of India, China, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia. Borders here constantly changed over the centuries as invaders and traders came and went, destroying and rebuilding.

Ta Prohm, another ruined complex, revealed what happens when the temples are abandoned and nature takes over. Tree roots and branches worked their way into, over and along walls and penetrated buildings, toppling facades and breaking apart whole structures. The effect was beautiful, exotic and eerie all at once.

Following two days at Siem Reap, our Pandaw group boarded two half-filled buses for a five-hour drive south across the Cambodian countryside to meet the RV (river vessel) Mekong Pandaw.

During the rainy season, Tonle Sap Lake rises sufficiently to allow boats to operate directly from Siem Reap, but this was March, when water levels are at their lowest.

All manner of traffic was vying for space on the main highway — trucks laden with goods and riders on top of them; motorbikes with produce piled high for market or with whole families aboard; draft animals pulling heavy wooden wagons; local and long-distance buses; and cars, but not many.

Boarding Mekong Pandaw

Arriving at the river city of Kampong Cham, we drew up to the edge of the Mekong embankment and had our first look at the Mekong Pandaw, home for the next week. The bow had been run up against the bank below, and lines fanned out to be wrapped around tree trunks. Immediately, I thought of the dear old Delta Queen moored along the Mississippi.

Our 200-foot boat below had a three-deck teak superstructure set on a black hull with white wooden sections that enclosed the forward lounge and galley aft. A black funnel rose in the gap between white canvas awnings covering the top deck.

Though built only a dozen years ago, it looked enchantingly colonial with accommodations for 64 passengers, while there would be just 35 on our voyage.

With the river level so low, we received assistance from the crew clambering down the embankment to reach the gangway. The captain greeted us, a steward handed out cold towels, and another showed us to our stateroom, where our bags had already arrived.

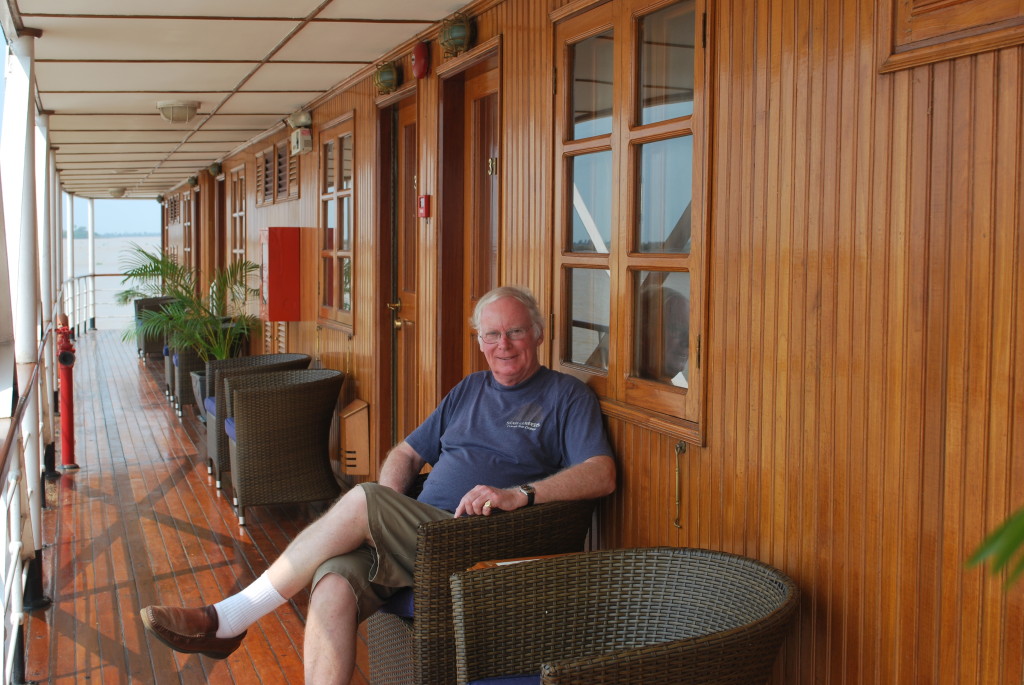

Cabins were arranged on Upper, Main and Lower decks and ours, 309, was on Upper. The cabin had twin wooden bunk beds with deep drawers beneath, vertical teak paneling, two-tone wooden doors — louvered for the closet and bathroom (with stall shower) — a vanity with more drawers, wicker stool, wooden luggage stands, two screened windows, and shiny brass handles and knobs. The bulkhead above was painted white, separated into squares by medium tone wooden stripping. For cooling, the cabin had a ceiling fan and air-conditioning with individual controls.

The cabin door opened onto the side promenade, dotted with potted palms and two wicker chairs set at either side, a relaxing location for reading while we made our way down the Mekong from Cambodia into Vietnam.

For the initial welcome, we all gathered on the Sun Deck (running the boat’s full length) and sat in rattan chairs and settees under the protective awning. A bar was set up at one end and a pool table at the other, with deck chairs in various groupings in between.

The Vietnamese purser welcomed us, laid out the plan for the days ahead, and introduced us to the Vietnamese, Cambodian and Burmese officers and crew. We felt in very good hands for the adventure ahead.

Half the passengers were Australians, and the rest were equally divided among Americans, Brits, Swiss, and Germans — with the latter two nationalities speaking very good English.

Dining Aboard Mekong Pandaw

Following drinks, hors d’oeuvres, and a briefing about the next day’s activities, the dinner gong sounded, drawing us two decks below to the restaurant, set out with rectangular tables for six, easily expanded to eight. Tall french doors, open at breakfast and lunch, brought in the breezes, while at dinner with the evening rise in humidity, they were shut and the A/C switched on. No time of day was ever uncomfortable here or up on deck as long as one stayed out of the direct sun.

Dinner the first evening produced green papaya seafood salad with peanuts as an appetizer, then broccoli soup followed by three entrees that were put on the table for all to share: two freshly grilled whole fish from the South China Sea, chicken curry, and steamed vegetables. On other nights, we ordered from a menu or again had a choice of three entrees brought to the table. Cambodian and Vietnamese beer and soft drinks were complimentary, and imported wine purchased from a list.

Breakfast, a buffet, had eggs to order. Lunch, also buffet-style, offered stirfry dishes and fresh pasta along with both hot and cold (not spicy) Southeast Asian and Western dishes — one treat was grilled crocodile with balsamic vinegar. Everything was well prepared and nicely presented.

One night our table received a bit of a jolt when an English passenger, who had taken lunch in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, returned with a doggie bag. Its contents contained two grilled tarantulas, now considered somewhat of a delicacy but once were a survival food during the Khmer Rouge period (more about that later). I was game to crunch on one of the legs, but not the body nor the head.

On the deck above the pilothouse, the air-conditioned lounge bar, attractively furnished with comfortable armchairs and settees, served as the evening venue for films or borrowing a book. Otherwise, most gravitated to the top deck to enjoy the open air, under a canvas cover.

The First Landings of Mekong Pandaw

The Mekong Pandaw reversed into the river and headed downstream, tying up below Wat Hanchey, a pagoda complex with a monastery for monks and nuns, school, and recreational playground set high up on a hill. The tree-shaded place was just coming to life for the day with vendors preparing food for lunch and monks sweeping the pavement.

We visited a Hindu temple, walking among small Buddhist temples and mausoleums. The children showed us their school, its grounds partially surrounded by colorful statues of animals and fruits that they cheerfully identified for us in English.

Later in the day we visited an orphanage, home for a hundred children supported by the government and private donations. As requested, we came bearing useful gifts from a local market such as pens, pencils, writing tables and notebooks The kids attended a local school and had learned English and French at the orphanage. During the visit, they showed us their paintings, drawings, and handmade clothing that were for sale.

After dark we met the Indochina Pandaw, bound upriver, its powerful spotlight trained on us – and ours on them. The other boat was of a slightly different design with a pilot house high up and forward while ours was on the lowest deck just behind the bow. We exchanged greetings and some needed tools and went on our way.

At Kampong Chhnang the Mekong Pandaw tied up to a pontoon, and we boarded launches to tour the floating Vietnamese community, housing some 1,000 refugees that fled South Vietnam in 1979. The colorfully painted wooden houses, built on rafts, had outboard motors attached to shift them when the rising river required a safer anchorage. Market boats plied the waterway selling produce to the residents, many of whom lived by fishing and operating fish farms.

The launches dropped us onshore, and we walked through a huge market with purveyors seated behind tables or sitting on the pavement selling food grown in the countryside and brought in by bus, motorbike or bicycle, or fished from the nearby waters. Blacksmiths were busy repairing tools, barbers giving haircuts and roadside cooks preparing meals. At streets that ended down at the Mekong, ferries loaded two- and four-wheel vehicles, heaps of freight, and foot passengers for the river crossing.

Phnom Penh & The Killing Fields

Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s stylish capital, became the most poignant and contrasting stop of the entire week. On one hand we visited the impeccably maintained gilded Royal Palace with its silver-tiled floors and French-era National Museum, a handsome repository for Cambodian history and Angkor period sculpture, and traveled the tree-lined boulevards streets and narrow streets by trishaw.

On the other we came face to face with the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge (1975-1979) period, when a communist Cambodia government headed by Pol Pot forced the entire population to vacate the capital for the countryside to take up work as peasant farmers; the resulting starvation, disease, brutal torture, and killings resulted in an estimated two million deaths.

We learned about the extreme torture treatments at S21, a former school — and now genocide museum — that was turned into a prison with isolation cells built inside the classrooms. Today, its walls are lined with photos of those who were killed, including most of the female workers. We saw gruesome pictures of the tortures that imprisoned artists were forced to paint.

The revelatory 1984 film The Killing Fields — screened onboard our riverboat the previous evening — was a grim preparation for our drive out to one of the Killing Fields. Empty pits showed where an estimated 17,000 bodies had been dumped, and the centerpiece was a Thai-style memorial tower housing row upon row of skulls and bits of clothing.

Our guide told us that when the Khmer Rouge came to the house to take his family away for execution, one of the executioners recognized his father from when they had been monks together. The immediate family was spared, but not the grandparents, aunts or uncles. It was hard to reconcile such violent recent history against today’s peaceful travel experience.

Crossing into Vietnam

As we entered the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, the now sluggish river split into nine branches and further into a network of connecting channels, resulting in heavily-trafficked river highways crowded with fast and slow passenger boats and barges carrying farm produce, wheat, coal, gravel, bricks, and containers. From the Sun Deck, we watched all manner of stuff slide by, and when passing through towns, the frequent cross-river ferries had the captain hard on his whistle to clear the way. Typically, the ferries did not change course, so we did, to avoid collision.

At Sa Dec, we passed several miles of brick factories, then docked at one to watch the process. Wet clay was carried to machines for turning into hollow bricks, then the excess cut away and individual bricks stacked and carted to kilns for firing. Much of the repetitive work done by hand or by very small machines worked by both men and women. The finished product was then transferred to river barges for distribution.

At Cai Be, the Mekong Pandaw maneuvered its way through a floating market where individual houseboats identified what they were selling by tying a bunch of bananas, a coconut or a dried fish to a bamboo mast. Onshore, we walked along wooded footpaths through a village where residents were working out front of their houses weaving baskets, seated at looms making cloth, or setting dung patties out in the sun to dry into fuel. They looked up and smiled as we paused to watch.

Transferring to Ho Chi Minh City

After enjoying a thoroughly insightful week, we disembarked for the 90-minute drive into Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon is still the official name for the city center) and a two-night stay at the InterContinental Asiana Saigon. The bustle and traffic of this energetic city on the move was in sharp contrast to the river’s slow pace and languid lifestyle. Evidence was everywhere that this is a country on the move, most vividly when crossing streets.

Our Pandaw Mekong river cruising experience was just about faultless and as insightful as a relatively short travel experience can be, and I now yearn for a longer trip on the Irrawaddy, the origin of Pandaw’s winsome style of river cruising.

Special Notice: US citizens must have visas for Cambodia (which can be arranged in advance or at most entry points), and for Vietnam (single- or multiple-entry visas have to be obtained in advance). Note: Make absolutely sure of the entry date at the river border from Cambodia into Vietnam — there is a financial penalty fee for alterations.

Don’t miss a post about small-ship cruising, subscribe to QuirkyCruise.com for monthly updates & special offers!

© This article is protected by copyright, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the author. All Rights Reserved. QuirkyCruise.com.

HEIDI SARNA

HEIDI SARNA