The Polar Code

QuirkyCruise’s Heidi Sarna had an e-chat about the Polar Code with Atle Ellefsen, Chief Naval Architect at the Oslo headquarters of DNV GL, a global foundation working in all business areas including ship classification and maritime advisory.

Heidi met Atle in 2000 at the Meyer Werft Shipyard in Germany, when Atle was director of new building for Royal Caribbean and Heidi was there to research a book she was writing about the line’s Radiance of the Seas, a big ship Heidi will always cherish.

Read more about Atle at the end of the post.

Q: What is the Polar Code and why is it important to small ship cruising?

Atle Ellefsen: The growth in maritime commercial activity in the Polar Regions has brought on new challenges and risks, not only for the ships that sail there, but also for the polar environment and those dependent on it.

In 2016, nearly 2,300 ships were operating in polar waters, and so the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted a new, mandatory Polar Code to provide for safe ship operation and environmental protection in the Polar Regions, on top of their foundational Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS)* and International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) requirements.

The Polar Code acknowledges that polar waters may impose additional demands on ships beyond those normally encountered.

Chief Naval Architect Atle Ellefsen, of DNV GL

The Polar Code came into force in January 2017 and it’s retroactive for old ships.

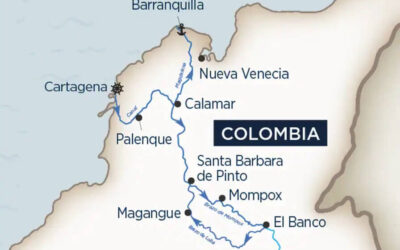

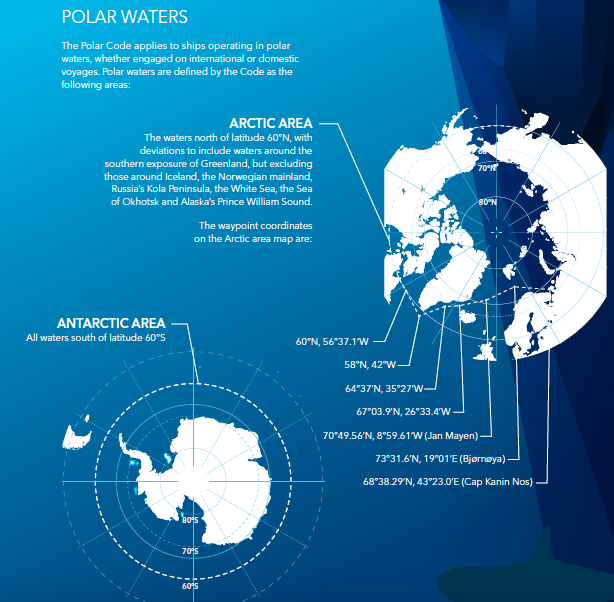

By 2020 all existing ships certified to SOLAS and sailing in polar waters, are expected to carry the Polar Code ship certificate. In the Antarctic, the Polar Code is in force in all waters south of latitude 60 ‘S; in the Arctic in all waters north of latitude 60 ‘N, with deviations to include southern Greenland and Svalbard, but excluding Iceland and Norway.

Credit: DNV GL

The intent of the code is to increase safety and mitigate the impact on people and the environment in the remote, vulnerable and harsh polar waters. There are a number of requirements specific to passenger ships, for example to lifesaving equipment, stability and redundancy depending on the vessel’s polar code category, ice class, polar service temperature, and itinerary — all of which has to be decided by the cruise line. There are no requirements that differentiate according to the size of the cruise ship, or the number of passengers.

Whether large or small, cruise ship or cargo ship, the Polar Code is equally applicable.

Click here for more details on the Polar Code.

*All passenger ships in international trade over a certain size have to comply with the SOLAS’ “Safe Return to Port” regulation, which dictates that in case of fire or flooding in any room, all critical systems shall remain in operation with sufficient residual capacity to be able to return, on its own, to the nearest safe port — which in Antarctica may be over a thousand miles away.

The cruise ship Sea Spirit in front of a huge Iceberg in Antarctic Sound. Antarctic Sound is at the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and connects the Southern Ocean to the Weddell Sea. Even in the summer months it is often filled with huge tabular icebergs. * Photo: Poseidon Expeditions

Q: Who is responsible for enforcing the Polar Code?

Atle Ellefsen: The key entities are the IMO, flag states and port states.

The Polar Code is established and maintained by the United Nations through the IMO, and it is the ship’s flag state (or country of registry) that enforces its ships are compliant.

Classification societies (such as DNV GL, for whom I work) are also involved as authorized representatives of the flag states to certify ships on their behalf, and to handle the compliance, inspections and certifications that go along with it. In this role, class societies are enforcing the flag state’s regulations, not the class societies’ own rules.

To maintain a ship’s polar certificate, it is regularly boarded for inspection (announced and un-announced) by officials from the flag state, the classification society and/or various maritime authorities of the host country. If the ship does not have all certificates and permits in order, including the polar certificate, she could be detained and the company fined.

Q: How has the Polar Code evolved over the decades?

Atle Ellefsen: The Polar Code has developed over some 20 years. After years of discussions, in 2002 the IMO established the non-mandatory “Guidelines for Ships Operating in Arctic Ice-Covered Waters.” The intention was that these guidelines would cover Antarctica as well, but the Antarctic Treaty Parties (ATP) objected to IMO’s involvement, restricting the guidelines to Arctic waters.

This changed when the expedition vessel Explorer sank in Antarctica in 2007. With this, and an increasing awareness following a number of other accidents and near-misses in the Polar Regions, the ATP requested that the IMO extend the guidelines to Antarctica, which it did in 2010. The mandatory code was developed and finally implemented as the Polar Code in 2017.

Q: How does the Polar Code affect passenger ships?

Atle Ellefsen: Fundamentally, a ship owner identifies which hazards of the polar environment are relevant to the ship and then implements designs and operational measures to effectively alleviate the hazards.

The Polar Code affects almost all aspects of a ship and has to be considered from the minute an idea for a new ship is scribbled on a napkin through to its design, construction, testing and delivery.

The Polar Code requires that:

- Every piece of steel, and all the ship’s machinery and systems, need to be assessed in terms of frigid temperatures and treacherous waters. This may require special technical solutions such as de-icing on exposed equipment, controls operable by crew in bulky clothing, and materials be able to retain their mechanical properties without cracking or becoming brittle.

- Enhanced lifesaving equipment is also necessitated for passenger ships, such as heated, enclosed lifeboats with long-range fuel, provisions and water capacity, and also outfitted with thermal immersion survival suits, sleeping bags and tents.

- The ship must have voice and data communication with shore anywhere within its operational area, be able to detect ice in darkness, and maintain the required stability margins with thirty millimeters of accumulated ice on deck, which on a typical exploration cruise ship amounts to over a hundred tons topside.

- The hull may have to be reinforced in order to sail in ice, depending on the severity. Most polar exploration cruise ships are strengthened for light ice conditions.

For new ships, the Polar Code assessment is carried out with the shipyard at the very beginning of the design phase. Here the owner needs to decide where and in what ice conditions to sail, and determine the lowest temperature in which to operate, the so-called Polar Service Temperature (PST).

My company, DNV GL, has a designated team of consultants working full time with owners and yards, guiding them through the labyrinths of the Polar Code.

Q: Could climate change, especially the warming of the Arctic region, affect the Polar Code in the future?

Q: Could climate change, especially the warming of the Arctic region, affect the Polar Code in the future?

Atle Ellefsen: As temperatures warm and ice conditions become less difficult, then a ship will likely be able to go places tomorrow that it cannot go today — ironically, cruise ships themselves are one of the contributors to global warming. That said, I don’t foresee changes to the Polar Code because of global warming.

Poseidon Expeditions in Antarctica. * Photo: Poseidon Expeditions

Q: Does the Polar Code inform the design of new technology, such as the X-Bow?

Atle Ellefsen: It’s more likely that commercial factors steer the development of new designs and technology for passenger ships plying the Polar Regions — for example to appeal to the ultra-luxury segment, or designs to enable budget cruising.

Suppliers and shipbuilders are continuously developing their products, improving performance, environmental impact and energy consumption. As you would expect, equipment for polar use is more sophisticated, rugged and expensive than standard cruise ship equipment.

Ulstein’s X-bow, for instance, was designed to improve seakeeping on offshore support vessels in the North Sea. Especially on standby ships to offshore oil platforms that face strong waves, the effect is remarkable compared to wide, flared bows and might reduce sea spray and thus icing in polar waters. The X-bow can be, like most traditional bows and hulls, built with the required ice strengthening for polar passenger cruising, however it’s not the only bow type that performs well in heavy seas and in ice.

Only ice-breakers have purpose-built bows, designed to slide up on the ice and by its sheer weight crush down on it.

Ulstein’s X-bow on the SunStone’s upcoming new builds. * Photo: SunStone

More about Atle Ellefsen

Atle started designing ships as a teenager and his career path was laid out after graduating with a master’s degree in naval architecture and maritime technology from the University of Trondheim, Norway. A fellow member of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects, he has worked in almost all areas of ship design, shipbuilding and management. He had his own design business for 10 years, and for six years he was Royal Caribbean’s newbuilding project director, developing and overseeing the cruise line’s projects in France and Germany.

Atle currently holds the position of chief naval architect in DNV GL maritime advisory, assisting ship-owners in devising new, innovative concepts; shipyards in improving capabilities; and financiers with due diligence on maritime investments. Working with top managers worldwide, he is a specialist on cruise ships and has in the last few years assisted the increasing number of owners and yards new to the cruise industry. Atle has three children, and in his spare time he enjoys dabbling in art and sailing his yacht.

© This article is protected by copyright, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the author. All Rights Reserved. QuirkyCruise.com.

Q: Could climate change, especially the warming of the Arctic region, affect the Polar Code in the future?

Q: Could climate change, especially the warming of the Arctic region, affect the Polar Code in the future?

HEIDI SARNA

HEIDI SARNA