By Ted Scull.

DELTA QUEEN is tied up for the day at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. * Photo: Ted Scull

My ties to Mississippi River Cruising run deep. As a map lover, I have always liked tracing rivers from their mouths well into the interiors of countries and continents — the Amazon in South America, Danube in Europe, Nile in Africa, Yangtze in China and domestically, America's Mississippi River in the US of A. Geography and history reveal the rivers’ individuality and importance as water highways for exploration, settlement, trade, and invasions. At first, I did not think of them as travel arteries as one might think of cars on highways and trains on railways.

I first saw the Mississippi River when I crossed it by train into St. Louis and then a few years later ferried across the river in New Orleans to a place called Algiers. It seemed big, sluggish and not particularly beautiful.

A ship enthusiast organization I belonged to asked me to be a US-flag ship history speaker during a week’s Mississippi river cruise on the sternwheeler Delta Queen, the legendary steamboat dating from 1927. As I had the summer off from my teaching post, I accepted, not knowing much about the boat, other than a bit from my parents. In the mid-1960s they had traveled aboard the Delta Queen with five other couples, or three tables of bridge. They joined the DQ at Cincinnati for New Orleans. My father found the boat quaint, while my mother was cheerier about the trip, probably as she came from the Midwest and also liked to travel. I think, as often happens, it was bridge morning, noon, and night that consumed most of their interest.

When it was my turn in August 1985, I rode Amtrak from New York to Chicago and into St. Louis arriving via the famous 1874-built Eads Bridge across the Mississippi that carries trains on one level and cars the other, and finally a taxi from Union Station to the river landing.

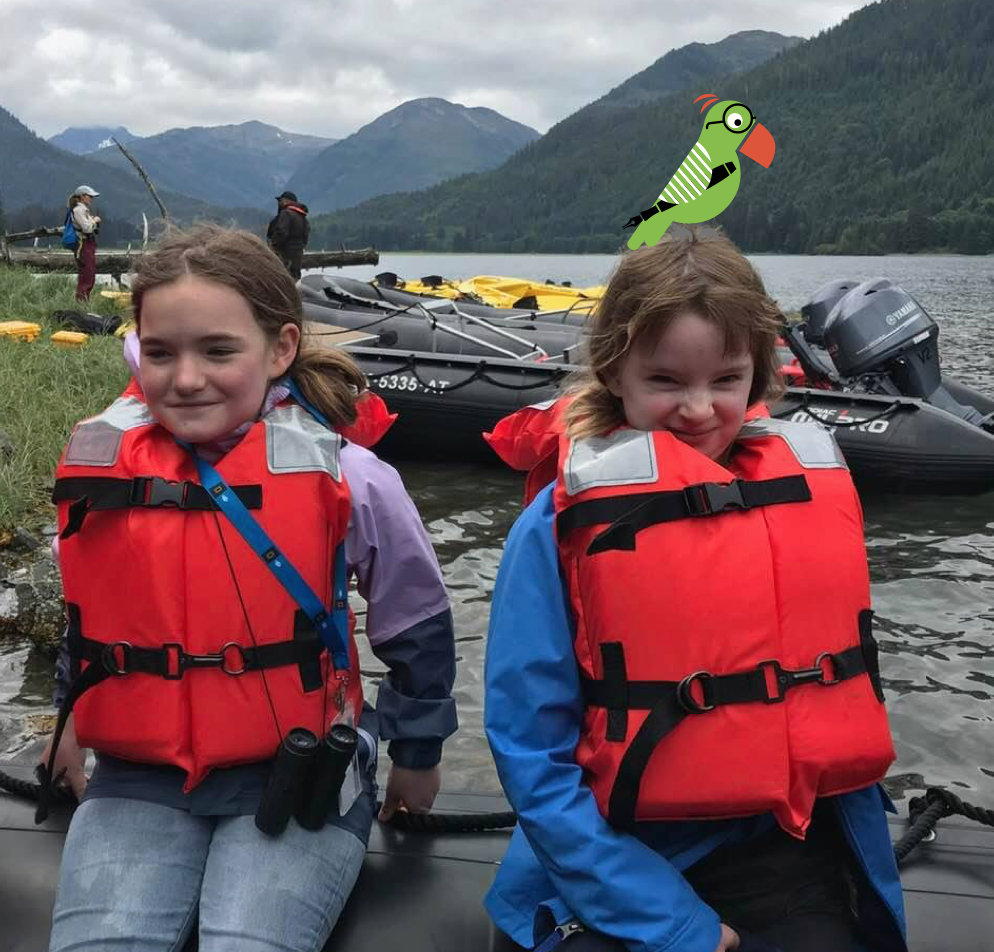

The steamboat Delta Queen appeared rather casually tied up with long lines reaching bollards far up the sloping bank. It was low water in August, while during the spring rains, the river was much higher.

A ramp (or stage in steamboat lingo) connected the boat to terra firma. Aboard, I entered another world encased within a wooden and steel superstructure. A grand staircase with brass treads led up to the wood-paneled Texas Lounge, a cozy bar, to which I was drawn because the small of fresh hot popcorn. Windows afforded a 270-degree view and the transoms decorated with pretty stained glass river scenes.

Transom scenes in the Texas Lounge of DELTA KING, sister to DELTA QUEEN. * Photo: Ted Scull

On one deck, a block of cabins opened into a lounge furnished with comfy chairs and sofas and walls covered with memorabilia from when the boat operated on an overnight run between San Francisco and Sacramento, and then for decades by the Greene family as a cruise vessel. She plied the Mississippi River system from New Orleans north to St. Paul, from St. Louis and along the Ohio up to Pittsburgh, and into a half-dozen smaller rivers.

Interior lounge aboard DELTA QUEEN portraits of the Greene family who bought the steamboat for cruising. * Photo: Ted Scull

Most cabins opened to side promenades and canvas-covered chairs were placed next to the doors. All the way aft Deck, a calliope awaited its player when we would announce our departure, imminent arrival (steamboat’s a coming) or met a barge and tow.

I was sharing another world with many others, some so in love with this authentic link to the past that they had made scores of trips and over as many different rivers as money would allow. After seven days of cruising the Mississippi and Ohio, then the Cumberland and Tennessee to Nashville and back, I got the bug too. That thrashing red paddlewheel provided genuine propulsion and was attached to long Pitman arms that rhythmically rose and fell in unison. I had fallen in love with Mississippi River cruising.

The crew hailed mostly from the South, many African Americans, and quite a few had been with the boat for years. The food was southern, Cajun and unabashed Midwestern; the entertainment New Orleans blues and jazz, the towns most welcoming, each with something to show off — a Civil War battle site; doll, quilt, or toy museum; large historical murals painted on flood walls; pretty main streets; and in Nashville, the Grand Old Opry.

A person known as the riverlorian kept us informed where we were, talked about navigation, told tales of floods, boiler explosions and fires, groundings, carrying troops and cotton, and of course, the origin of showboats where the performance took place on the stage, that is the ramp we used to come aboard with the audience gathered on the riverbanks.

When the fog descends, the DELTA QUEEN can swing out the stage and tie up almost anywhere until it lifts. * Photo: Ted Scull

By the time we returned to St. Louis, I was hooked and wanted more. Over subsequent years, I made five trips aboard the Delta Queen, one with the mid-1970s Mississippi Queen, also a true steamboat, and two with the present lavishly-outfitted American Queen, sailing navigable stretches of the Mississippi, Ohio, Cumberland, Tennessee and Kanawha. The steamboats were as different and enchanting as were the rivers and places we landed. I have also sailed with American Cruise Lines a half-dozen times, but not on the Mississippi.

AMERICAN QUEEN on the Lower Mississippi. * Photo: Ted Scull

Whomever you go with, the overall experience is much the same, visiting similar and diverse towns and cities, all with a story to tell, in the company of folks who want to see more of their own country and served by crews who share their own stories, from the captain to the engine, cabin and dining staff. A living slice of history thrashes on aboard a Mississippi and Ohio steamboat.

![]()

HEIDI SARNA

HEIDI SARNA